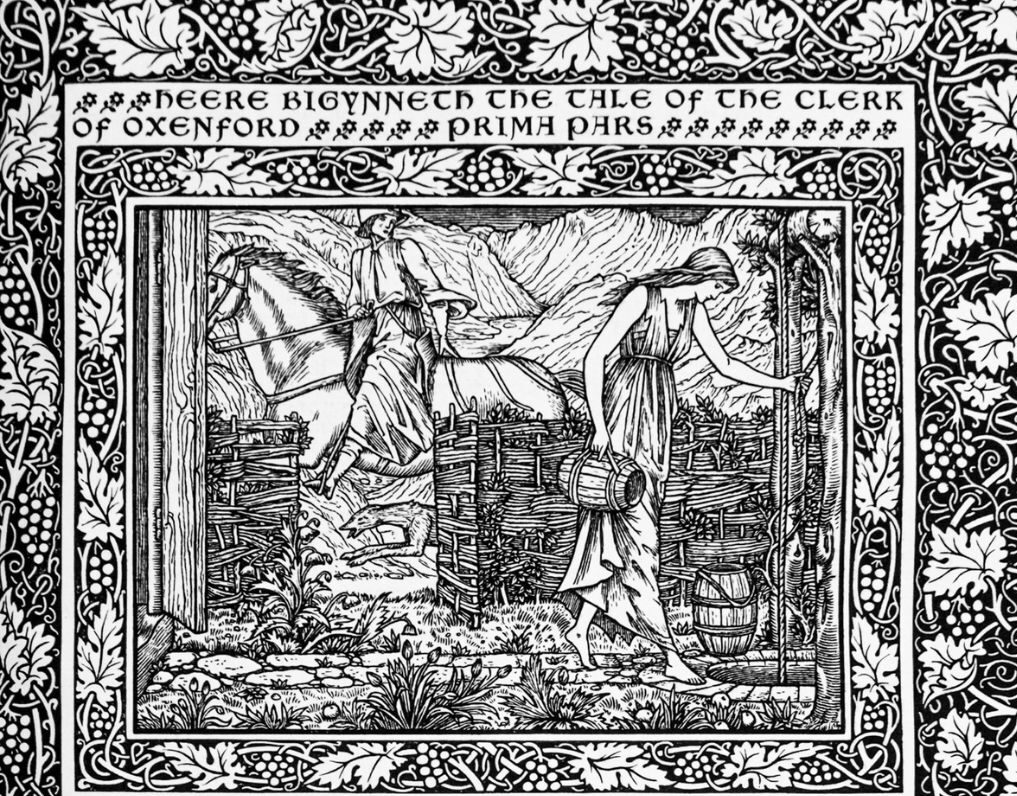

Detail from Geoffrey Chaucer, The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (London: Kelmscott Press, 1896); Pequot Library Special Collections, gift of Elizabeth Flack in memory of Robert Flack

by Cecily Dyer, Special Collections Librarian

On an autumn evening in 1888, William Morris arrived at the New Gallery in London to hear his friend, neighbor, and fellow socialist, Emery Walker, deliver a lecture on letterpress printing for the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Walker was uneasy as a presenter, but the examples of beautifully-designed 15th-century typefaces that his lantern slides projected on the wall mesmerized the audience, Morris in particular. At 54, the restless Morris had already made significant accomplishments as a designer, poet, reformer, environmentalist, architectural conservationist, and more—all while his political activism led to him being surveilled and twice arrested—but he had never designed a typeface or had his own press. As he departed that evening, he said to Walker, “Let’s make a new fount of type,” a suggestion that would lead to Morris’ last creative endeavor: the Kelmscott Press.

Privately-printed books were an ideal vehicle for Morris and others to promote and realize the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement, which held that traditional craftsmanship had produced beautiful objects and brought joy to the workers who created them, while the low-quality substitutes of the Industrial Revolution emphasized profit over craftsmanship and were made in factories ruinous to the environment and society. Like other movements of the 19th century, including Romanticism, the Nazarene movement, and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the Arts and Crafts movement rejected the Industrial Age, turning instead to the past—especially the medieval period—for inspiration, advocating for a medieval-style system of manufacturing based on small-scale workshops and guilds in order to achieve social and economic reform.

Morris designed and ornamented each of the Kelmscott Press’s 53 books, in defiance of the Industrial Revolution’s common practice of division of labor. The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer was Kelmscott’s crowning achievement—a 17-pound tome with Morris’ intricate borders, his “Chaucer” typeface, and seamlessly integrated woodcuts by his lifelong friend, artist Edward Burne-Jones. Most copies, including Pequot Library’s example, were bound simply in paper-covered boards and a linen spine, while a small number were spectacularly bound in white pigskin at T.J. Cobden-Sanderson’s Doves Bindery.

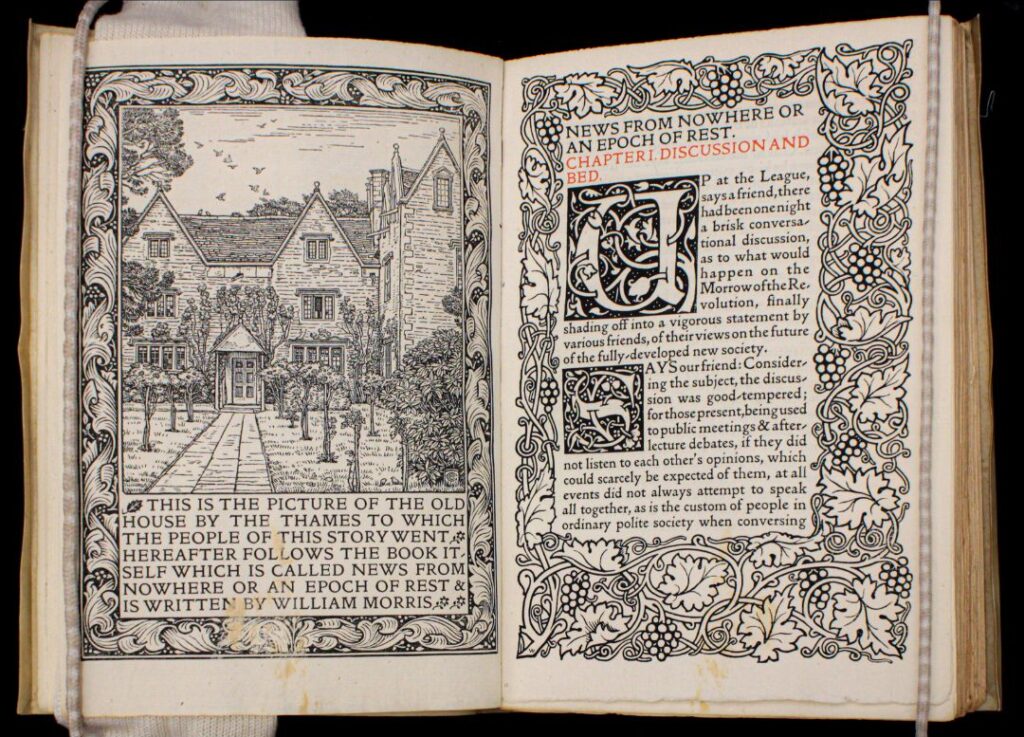

The Kelmscott Press offered Morris control not just over every aesthetic element, but also over the content of the books, so that nearly half of the Kelmscott publications were Morris’ own writings—a mixture of utopian, radical, and fantastic compositions. His novel News from Nowhere tells the story of William Guest, who falls asleep after returning from a meeting of the Socialist League (a real-life organization founded by Morris, Eleanor Marx, and others) and awakes to find himself in a future society where there is no private property, no authority, no monetary system, no marriage or divorce, no prisons, and no class systems. In this agrarian society based on common ownership, men and women work simply because they find pleasure in doing so–a response to the argument that without private property, there would be no motivation to work.

Although Morris died just five years after the Kelmscott Press issued its first book, his efforts launched the Private Press movement, where design, exceptional craftsmanship, and fair working conditions were emphasized over profit. One of the first to follow was C.R. Ashbee’s Essex House Press, which provided jobs to many of Kelmscott’s displaced workers after Morris’ death. In 1902, Ashbee moved the Essex House Press and his Guild and School of Handicraft to the town of Chipping Campden, where it would become one of the foremost workshops of the Arts and Crafts movement and a pioneering social experiment based on the movement’s principles.

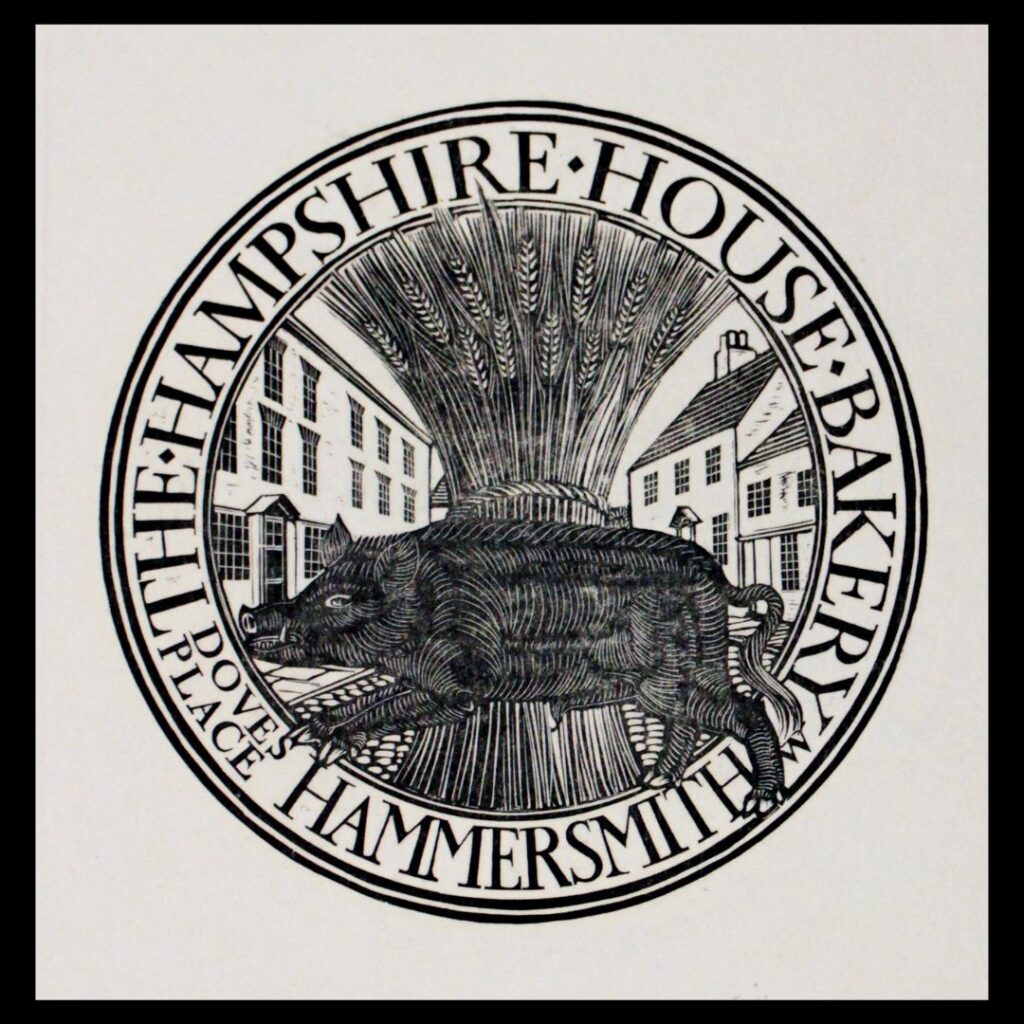

Even without the Kelmscott Press, the Hammersmith neighborhood remained a hive of Arts and Crafts activity. Emery Walker and T.J. Cobden-Sanderson founded the Doves Press there, which, along with Kelmscott, is considered one of the greatest private presses. Hammersmith was also home to calligrapher Edward Johnston and his student Eric Gill, as well as printer Hilary Douglas Pepler, who founded the neighborhood’s Hampshire House Workshops.

Even without the Kelmscott Press, the Hammersmith neighborhood remained a hive of Arts and Crafts activity. Emery Walker and T.J. Cobden-Sanderson founded the Doves Press there, which, along with Kelmscott, is considered one of the greatest private presses. Hammersmith was also home to calligrapher Edward Johnston and his student Eric Gill, as well as printer Hilary Douglas Pepler, who founded the neighborhood’s Hampshire House Workshops.

Pepler and Gill soon moved south to the village of Ditchling and converted to Catholicism, creating a medieval-style artist community and founding the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic. The Guild included St. Dominic’s Press, which printed books and broadsides that promoted community events and socialist ideals. Both the Kelmscott Press and St. Dominic’s Press carried influence in America as well–Kelmscott in upstate New York’s Roycroft reformist community of craft workers, for example, and St. Dominic’s in several presses intricately tied to Catholic social activists

and the Catholic Worker Movement.

The Arts and Crafts and Private Press movements died down as Modernism emerged, yet its inherent ideas have experienced periodic resurgences in the years since. One such moment occurred in the late 1960s and early 70s, which saw interest in returning to the land, communal living, promoting peace and a more equal distribution of wealth, as well as medieval-inspired fashions and folk songs like Scarborough Fair. William Fletcher, an assistant professor of sociology at Sacred Heart University and a lecturer on the art of the book, saw these ideas firsthand in his students and took the opportunity to introduce them to the works of St. Dominic’s Press, believing that seeing what the Catholic community at Ditchling had produced a half century earlier would provide historical context for his students and help them channel their energy into action. The collection he built and shared with his students, one he would later leave to Pequot Library, carried a message: making books can be a radical act, disseminating disruptive ideas in beautiful design.