by Jessie McEntee, Marketing Associate

Charles Buckles Falls

“Books Wanted”

Pequot Library Special Collections

Pequot Library mounted an exhibition in 2017 titled The Great War and the United States Home Front, and the library holds a large cache of vibrant posters from this era. The war came about during the “Golden Age of American Illustration,” when book and magazine illustration proliferated and technological breakthroughs enabled low-cost reproductions. Many iconic images were born, some of which have lasted to this day. For example, as this article from The Smithsonian explains “…the image of Uncle Sam pointing at viewers and saying, ‘I WANT YOU,’ created by James Montgomery Flagg, dates from 1916 and was subsequently used throughout the rest of World War I, repurposed for World War II, and is still identifiable to many people today.”

Charles Buckles Falls or C.B. Falls (1874 – 1960)

A member of the Society of Illustrators, C.B. Falls produced war propaganda for the Division of Pictorial Publicity. The poster “Books Wanted” brought him great recognition. Supposedly, Falls created this poster in 24 hours, and the same image appeared on bookmarks identifying libraries as a “War Service Library.”

The poster was part of an American Library Association initiative. According to the Library of Congress, the ALA “maintained libraries for servicemen both at home and overseas through its Library War Service directed by Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam. Artist Charles Buckles Falls, who signed this poster with only an ‘F,’ designed a number of World War I recruitment posters, as well as those encouraging Americans to donate books and soldiers to use camp libraries. Between 1917 and 1920, some seven to ten million books and magazines were distributed.” Read more here.

Backing up for a moment, one might ask why the American government felt compelled to turn to propaganda in drumming up support for the war. As this article explains, “In 1917, the United States was not ready to fight… Not only was its military undersized, but its economy and society were unprepared for the commitment required to wage war in the 20th century.” As we’ll discuss below, Europeans also found themselves largely unprepared for the psychological toll of protracted conflict, in part because “in the century between Waterloo and the outbreak of the First World War, few wars were fought in Europe. Those that did occur were relatively limited in impact and duration” according to this article from the BBC History Magazine.

Image: Wikicommons

George Herbert Clarke (Editor)

A Treasury of War Poetry: British and American Poems of the World War 1914-1917

New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1917

Pequot Library Special Collections

In contrast to the plucky war poster seen above, the reality of living through World War I quickly proved to be grim. As per this article from the Imperial War Museum in London, “This was a scale of violence unknown in any previous war. The cause was to be found in the lethal combination of mass armies and modern weaponry. Chief among that latter was quick-firing artillery. This used recuperating mechanisms to absorb recoil and return the barrel to firing position after each shot. With no need to re-aim the gun between shots, the rate of fire was greatly increased.” Shells and small arms had also become more gruesomely effective than ever before due to technological innovations. The death toll ultimately reached 20,000,000, with 21,000,000 people injured.

Poetry written during this time underscores the public’s shift in sentiment as the chaos unfolded. According to this Poetry Foundation entry, “poems in 1914 and 1915 extoll the old virtues of honor, duty, heroism, and glory, while many later poems after 1915 approach these lofty abstractions with far greater skepticism and moral subtlety through realism and bitter irony. Though horrific depictions of battle in poetry date back to Homer’s Iliad, the later poems of WWI mark a substantial shift in how we view war and sacrifice.” Indeed, this 1919 review from The Atlantic speaks about the second edition of A Treasury of War Poetry (we hold a copy of the first edition in our Special Collections). The reviewer observes how the poems in this collection focus on the human cost, writing, “Professor Clarke’s anthology, like others, lays stress on these heroic qualities rather than on feats of arms.”

Literature published in the war’s aftermath showed a new interest in clear-eyed and unflinching realism. Think of classics like A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, a copy of which we also hold in our Special Collections. Modernism emerged as a forceful literary movement, seen in the works of James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, DH Lawrence, TS Eliot, and Ezra Pound, among others, all of which appeared in print from the 1920s on. Read more in an article from The Irish Times here.

Clare Leighton’s personal diary

Pequot Library Special Collections

Pequot Library acquired a collection of Clare Leighton’s books and papers in 1989 through a bequest of Reverend William Dolan Fletcher. Leighton illustrated 63 books in her lifetime, beginning in the 1920s, many of which showed her admiration for the simplicity and rhythms of gardens and rural life.

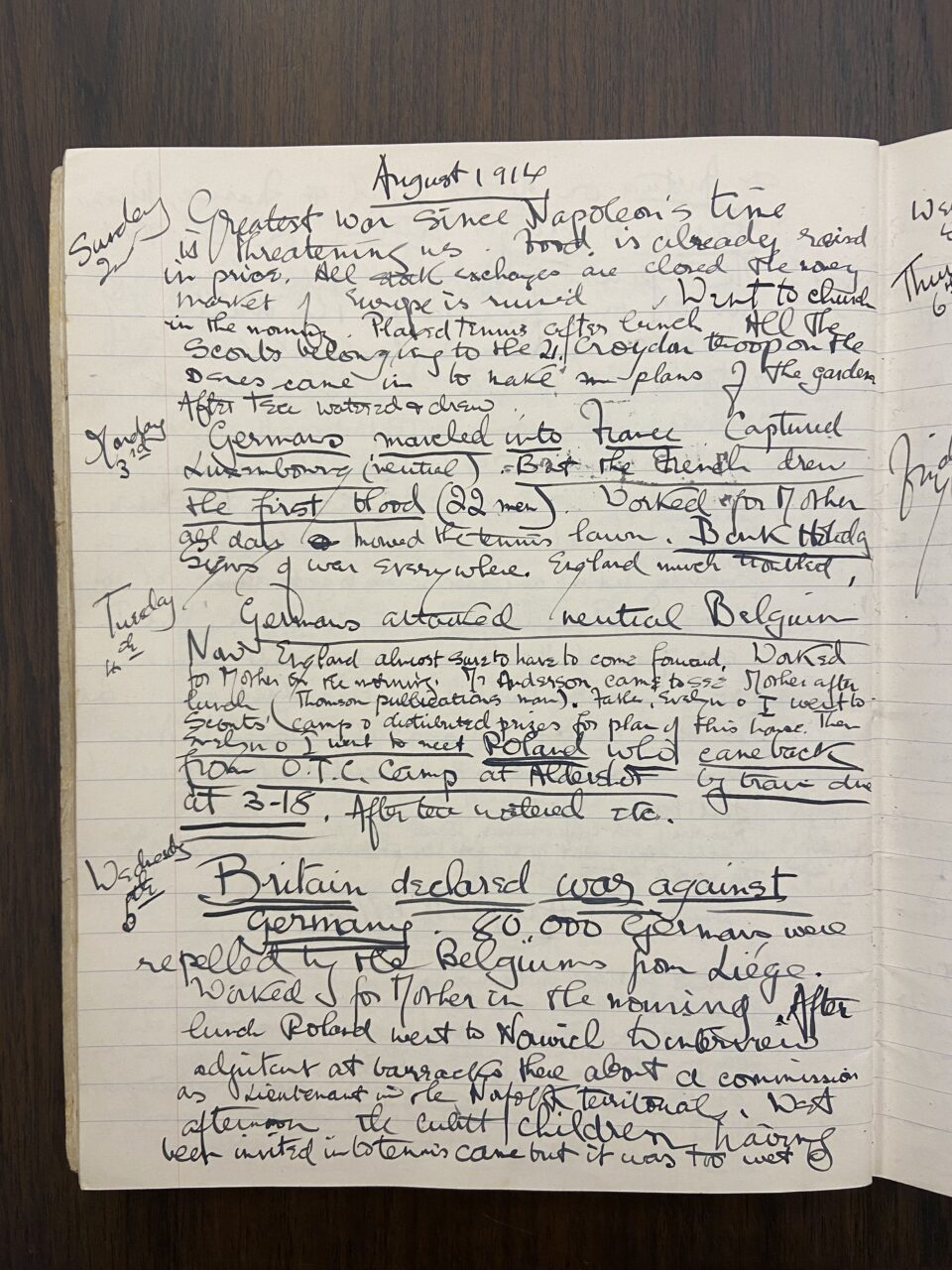

Leighton was born on April 12, 1898, in London, England, and came of age during the first and second World Wars. Her entries echoed the wartime experience mentioned above: her mood quickly deteriorated as shock set in. When she began her diary for the year 1914—seen above—she was a 15-year-old focused on her art and pining for a young man she referred to as “SS”, who had recently sat for a portrait. Presumably referring to SS, she wrote, “I can’t help feeling my heart thumping in my head whenever I see him — I can’t help my blood running through me — or rather gushing all way through me — hot and cold — when my hand is in his.”

One early diary entry reads as follows:

Monday, August 3rd: Germans marched into France. Captured Luxembourg (neutral). But the French drew the first blood (22 men). Worked for Mother all day Mowed the tennis lawn. Bank Holiday. Signs of war everywhere. England much troubled.

Her days revolved around helping her mother, sketching and working in the garden, and taking classes. Soon, however, the war enveloped much of Europe and, as mentioned in Leighton’s passage above, England itself. Leighton soon wrote of rising food prices, falling markets, and witnessing the arrival of starving refugees, and of learning that “SS” will be going off to fight.

The following year, Leighton’s older brother, Roland, a poet, died in action. Her later work as an artist reflected the trauma of her experiences during this time period. As this article from Smith College says, “A pacifist in a time of turmoil—her nineteen-year old brother and many of her friends died in the first world war—her prints reinforce man’s connection to the earth, and present a powerful alternative to the destruction around her. She felt compelled to preserve her vision of rural life to paper, too, in light of the rushing industrialism that destroyed the environments around her.”